Architecture is best understood when both the high-level design and the rationale behind that design are documented. Traditionally, architecture diagrams live in slide decks or wikis, and decision rationale lives in someone’s head (or buried in long documents). This often leads to outdated diagrams and forgotten reasons for past decisions. To solve this, I adopt a “documentation as code” approach, using tools like Structurizr for diagrams-as-code and Architecture Decision Records (ADRs) for capturing decisions. These techniques bring architecture documentation into the development workflow, keeping it version-controlled alongside the code. The result is living documentation that architects, developers, and DevOps engineers can collaboratively maintain, with less chance of it turning into stale “shelfware.”

In this post we’ll explore what Structurizr and ADRs are, how they work, and how they can be used together to document cloud and microservices architectures. We’ll discuss how ADR tooling (like adr-tools) influence the decision-writing process, and compare using Structurizr’s free “as-code” options versus its paid services. Especially in terms of enabling collaboration (even with non-developers) when all documentation is kept alongside code in each repo.

So what exactly is this Structurizr?

Structurizr is an open-source toolset for creating architecture diagrams using code. Created by Simon Brown (author of the C4 model), Structurizr embraces a “Diagrams as Code” philosophy. Instead of dragging boxes and arrows in a GUI tool, you write a definition using the Structurizr DSL or libraries in languages like Java and C#, that describes your systems, containers, components, and their relationships. Structurizr then renders this model into diagrams. This approach brings several benefits:

-

Consistent C4 Model Views: Structurizr naturally supports the C4 model’s layers – Context, Container, Component, etc. You can create multiple diagrams from one model to show different levels of detail (e.g. a high-level system context vs. a detailed container diagram of a microservice). This is ideal for microservices architecture, where you might need an overview of all services and zoomed-in views of individual services.

-

Version Control and Traceability: The diagram definitions (DSL text or code) are plain text files. You can store them in your repository, right next to the application code. This means architectural diagrams are under source control, diff-able, and updated via code reviews. When the system changes, you update the model in code and regenerate the diagrams, no more outdated Visio diagrams lurking in SharePoint.

-

Automation and Integration: Because it’s code, you can integrate diagram generation into build pipelines. Structurizr provides a CLI to push and pull models from its SaaS or on-premises server, and exporters to formats like PlantUML and Mermaid. You can also generate a static documentation site or embed diagrams into other docs. For example, a team might automatically publish the latest architecture diagrams to an README.md or internal website whenever the model code is updated.

-

Single Source of Truth: One Structurizr workspace can define your whole architecture model. The elements in it (people, software systems, containers, etc.) are defined once and then included in various views. This avoids inconsistencies like one diagram calling a component “Order Service” while another calls it “Orders API.” It’s all pulled from the same model.

-

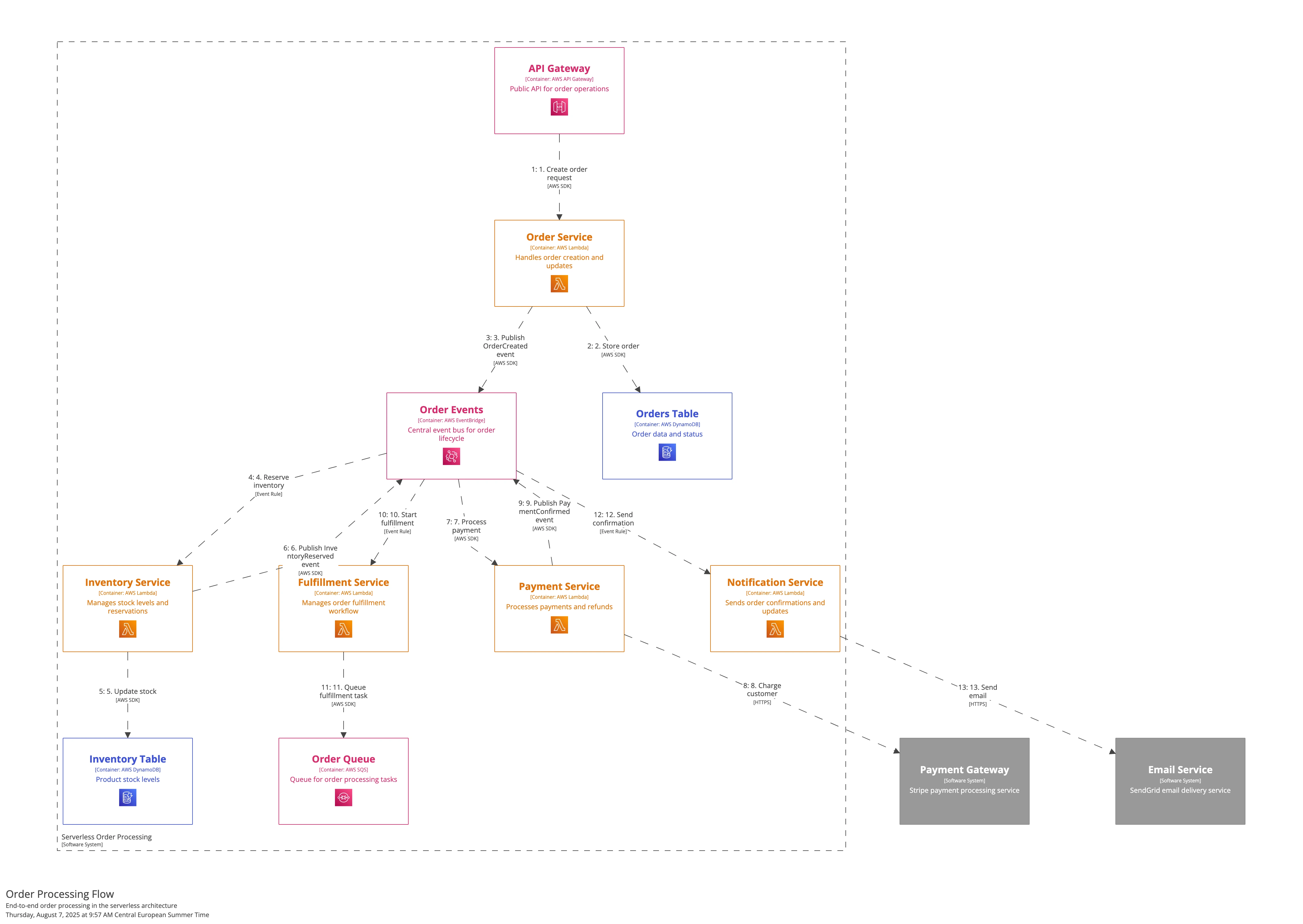

Cloud Architecture Support: Structurizr is well-suited for cloud systems. You can represent cloud services (AWS, Azure, etc.) as infrastructure nodes or deployment nodes in the model. Structurizr even provides an (AWS icon theme (GCP, Azure also included))[https://docs.structurizr.com/ui/diagrams/themes], so your diagrams can show official AWS icons for resources like API Gateway or Lambda. In code, you tag elements with specific AWS resource types, and the styling is applied automatically. This means your diagram of a microservice on AWS can visually include icons for an API Gateway, Lambda functions, SQS queues, EventBridge, databases, and so on, making it easy for readers to recognize cloud components.

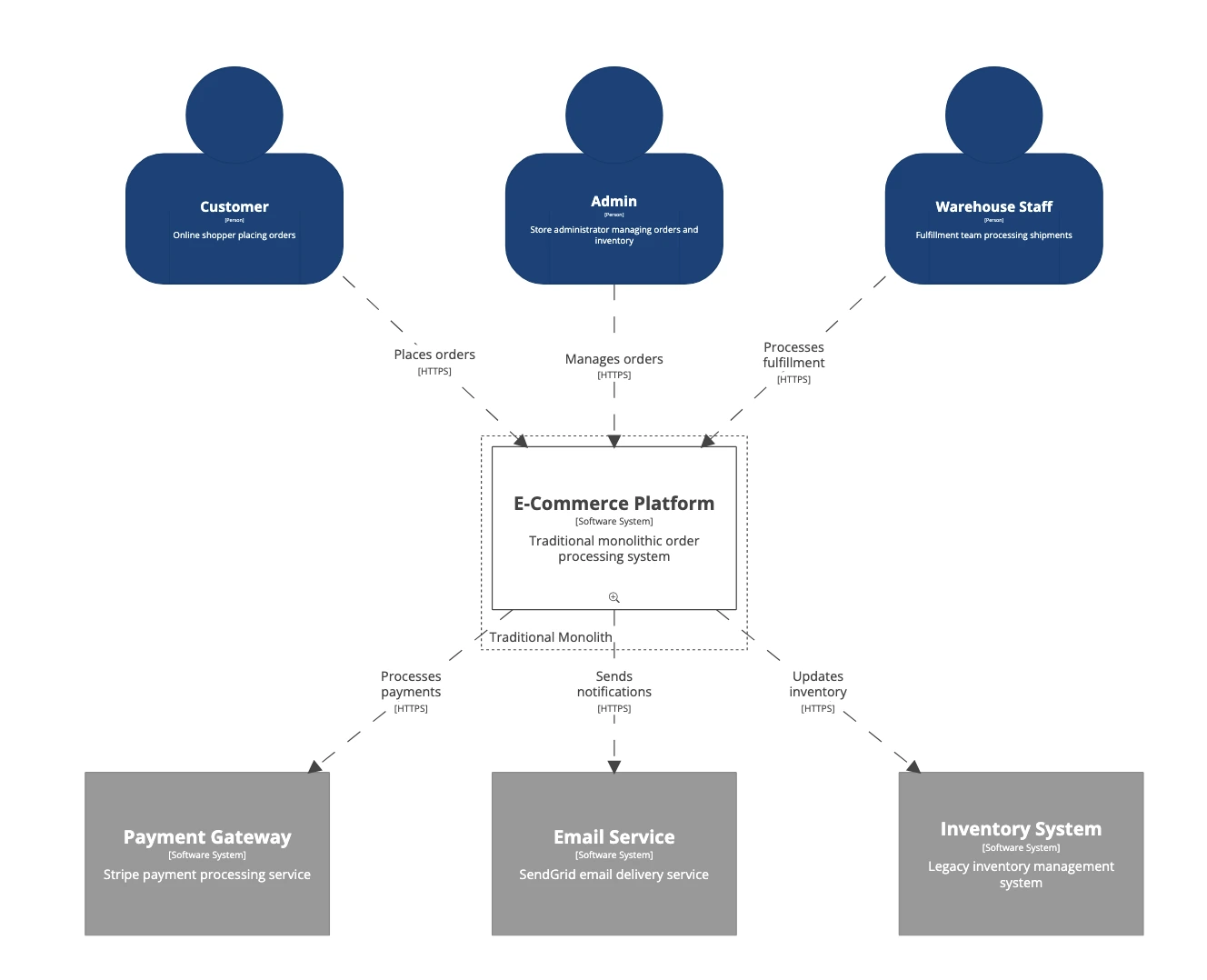

This diagram was generated directly from our Structurizr DSL model, the same model that can produce container views, component diagrams, and deployment views of this system. When a developer adds a new external service integration or changes system boundaries, updating the DSL automatically reflects these changes across all architectural views.

This diagram was generated directly from our Structurizr DSL model, the same model that can produce container views, component diagrams, and deployment views of this system. When a developer adds a new external service integration or changes system boundaries, updating the DSL automatically reflects these changes across all architectural views.

processing system

orders and inventory

shipments

service

service

system

Above diagram shows how Structurizr can export to Mermaid format, enabling the same architectural model to be embedded directly in documentation, README files, and GitHub wikis. This is particularly powerful for distributed teams where architects define the canonical model in Structurizr, but developers need quick access to current architecture in their daily workflows. The Mermaid export maintains the essential relationships and styling cues from the original model.

The key point is that Structurizr treats architecture diagrams not as one-off images, but as views derived from a coded model. This makes it much easier to keep diagrams in sync with reality. When your team refactors a service or adds a new component (say, introduces a new Lambda function for a feature), you update the model definition and regenerate – all diagrams update together. For cloud and microservices architectures that evolve rapidly, this approach ensures the documentation keeps pace with the code.

What are Architecture Decision Records (ADRs)?

While diagrams like those Structurizr produces show what the architecture looks like, they don’t explain why it evolved that way. This is where Architecture Decision Records (ADRs) come in. An ADR is a short text document that captures an important decision about the architecture, along with its context and consequences. Each ADR typically covers one key decision, for example: “Use an event bus (Amazon EventBridge) for inter-service communication” or “Adopt serverless functions for the Order service backend”.

ADRs were popularized by Michael Nygard, who proposed a lightweight template for recording architectural decisions

ADRs are saved as plain text (commonly md files) in your project’s repository, typically in a dedicated directory (e.g. docs/architecture/decisions or doc/adrs/). Because they live in version control alongside the code, they become part of the project’s history. New team members can read through past ADRs to understand why things are the way they are. And when changes are proposed, you can add or update ADRs via pull requests, allowing discussion and review of architectural choices just like code changes. In fact, ADRs can be considered “code” for architecture governance, lightweight and text-based.

Importantly, ADRs focus on significant, long-lived decisions. Not every code-level choice warrants an ADR. We use ADRs for the big choices that affect architecture and will be interesting to future maintainers e.g., choice of a messaging system, a major framework, a deployment strategy, domain design decisions, etc. ADRs provide context for these choices. For example, if one microservice uses AWS SQS queues while another uses EventBridge events, an ADR might explain the rationale (“Why do we have two different messaging approaches? – see ADR-0007 for the historical decision”). Years later, when someone asks “Can we unify our messaging system?”, they can find the original reasoning and see if it still holds.

Another nice aspect: ADRs aren’t limited strictly to “architecture” in the narrow sense, teams can also use them for recording other technical decisions or even process decisions. The key is the structured, changelog-like history of why things are the way they are. Think of ADRs as your project’s engineering journal.

Using Structurizr and ADRs Together

Structurizr and ADRs complement each other beautifully. Structurizr gives you the visuals, the maps of your system, while ADRs capture the narrative, the reasoning behind that map. Structurizr actually has built-in support to integrate ADRs into your architecture documentation. Because diagrams alone can’t express the decisions that led to a solution,Structurizr allows supplementing your model with a decision log. In practice, you can attach a folder of ADR Markdown files to a Structurizr workspace (using the !adrs directive in the DSL), and those records become accessible in the. Each ADR is parsed (title, status, content) and shown alongside the diagrams, giving readers an at-a-glance view of all key decisions in the architecture.

For example, imagine our AWS microservices system includes an ADR titled “Use EventBridge for Inter-Service Events”. In Structurizr’s web viewer, a team member could navigate to the “Decisions” section and find that ADR, seeing that it’s Accepted, the date it was made, and the reasoning (perhaps noting alternatives like direct point-to-point calls were rejected to reduce coupling). They could then switch to the diagram view and see EventBridge depicted, connecting certain services. The combination tells a complete story: the diagram shows what pieces like API Gateway, Lambdas, SQS, EventBridge look like in the system, and the ADR explains why those choices were made (e.g. “We chose a publish/subscribe model via EventBridge to enable decoupled asynchronous communication between services, improving scalability and fault tolerance”). As Structurizr’s documentation notes, this gives team members a quick way to browse decisions and understand the current architecture status.

Let’s consider a concrete scenario in a cloud architecture: say we have an e-commerce platform composed of multiple services. One service is an Order Processing service. The architects decided to go serverless for this component – API Gateway triggers a Lambda function for order submissions, the Lambda puts order details on an SQS queue, and a separate Order Fulfillment Lambda consumes from the queue. Why did they design it this way? Perhaps the ADR ADR-0005: Asynchronous Order Processing with SQS explains: Synchronous processing could slow user responses, so they chose to queue orders for downstream processing, trading immediate consistency for resilience. Meanwhile another ADR, ADR-0003: Use AWS Lambda for Order Service, cites reasons for going serverless (zero infrastructure management, auto-scaling on demand, etc., versus say running on EC2 or Kubernetes). These ADRs live in the decisions folder of the Order service’s repo. When maintaining the architecture docs, the dev team has included those ADRs in Structurizr. Anyone viewing the Order service’s container diagram in Structurizr can also click over to the decisions list and read ADR-0005 and ADR-0003, seeing both diagram and decision log in one place. This greatly aids understanding and onboarding.

From a DevOps perspective, keeping diagrams and ADRs in the codebase and in sync means your CI/CD pipeline can enforce consistency. For instance, you might have a job that verifies the Structurizr model was updated if certain config files changed, or simply a practice that every major architectural change (new service, new integration) should come with an ADR. This practice turns architecture governance into a continuous process, rather than a periodic review meeting with outdated diagrams.

Different flavors of structurizr

Structurizr is available in a few forms: an open-source library and DSL (which you use with the CLI or Structurizr Lite), a free cloud service (saas with limited features), and a paid cloud service (or on-premises product) with advanced features. All of them support the core idea of diagrams as code plus integrated docs/ADRs, but they differ in collaboration capabilities.

Structurizr Open-Source (DSL + CLI + Lite)

This is the completely free option. You define your architecture model using the Structurizr DSL or programmatically, and you can use Structurizr CLI or Structurizr Lite to work with it. Structurizr Lite is a local web application that runs on your machine (or could be hosted internally), it loads your workspace file and lets you view the diagrams, documentation, and ADRs in a browser. However, with the free tools there is no built-in server for sharing, no easy “share link” to send to a colleague outside the codebase. The expectation is that the diagrams or a published static site are shared via your own mechanisms. For example, you might commit exported PNG/SVG images to the repo or publish HTML pages via GitHub Pages. The good news is the open-source CLI can export diagrams to images and even export an entire documentation site as a single HTML file. In practice, teams using the free approach often generate a static site from the Structurizr workspace (diagrams + docs + ADRs all combined) and host that internally so non-technical stakeholders can simply open that site in a browser.

The limitations are mainly around multi-user collaboration in real time. Non-tech contributors cannot easily edit the diagrams without touching the code or DSL. If a product manager wants to suggest a change to a diagram, they might annotate an image or describe it in words, and a developer will update the DSL. In short, the free stack gives you full power for documentation as code, but requires a bit more effort to involve people who don’t work with the code. Still, since everything is text, even a non-coder could, for example, edit a Markdown ADR or suggest an edit via a pull request – it’s just not as point-and-click as a wiki.

Structurizr Cloud (Free tier)

The cloud service offers an easier way to publish and view architecture models online. With a free account, you get one workspace in the cloud. You can push your DSL model to Structurizr’s servers and then anyone with the account credentials can log in to see interactive diagrams and ADRs. The free cloud is great for a personal or open-source project, but it has it’s limits:

- supports a maximum of 1 workspace (so if you wanted each microservice in its own workspace, you’d need the paid tier or separate free accounts) and around 10 diagrams per workspace

- It also lacks some sharing features: notably, no read-only access links or role-based access control for others on the free plan.

In essence, the free cloud is for an individual, you can use it to host your project’s docs for yourself, but you can’t easily invite a team or stakeholders to collaborate there (unless you share your login, which isn’t ideal). Non-tech stakeholders in this scenario would likely still consume outputs via exported diagrams or a static site, because the Structurizr free cloud won’t allow them their own login to view (aside from making the workspace public if you choose).

Structurizr Cloud (Paid tier) and On-Premises

The paid version of Structurizr Cloud is designed for team collaboration. With a paid subscription, you can have multiple workspaces (e.g. one per repository or service, or one for each bounded context), and you can invite team members with read or write roles on those workspaces. Crucially, it provides sharing options: you can generate a secure read-only link to a workspace to share with anyone (even without a Structurizr account). This means, for example, you could embed an iframe of your live diagrams in a Confluence page or just email a link to an exec who wants to review the architecture. Paid accounts also include integration features that help bring non-developers into the loop: for instance, you can embed live Structurizr diagrams in Notion docs, or allow searching the architecture via Slack commands.

For example, Structurizr’s Diagram Review feature lets you create a review session with one or more diagrams, where reviewers (who don’t need accounts) can leave comments on specific elements, this is fantastic for design discussions, allowing architects and even non-technical stakeholders to comment on the architecture visuals directly. One thing to note: even in the paid UI, editing the content of the model (adding new elements or decisions) is still usually done via code or the DSL editor. The browser-based diagram editor is mainly for adjusting layout (moving boxes around) and not for adding new elements in freeform. So, if a non-developer wants to propose a structural change, they might not code it themselves, but the visibility and commenting features mean they can easily point it out and discuss it with the team. In summary, the paid Structurizr service doesn’t change what you document, but it significantly smooths how you share and collaborate on that documentation. It lowers the barrier for others to view the live architecture docs and give input without needing to touch Git or set up a local environment.

Embracing Structurizr and ADRs leads to a powerful outcome: your architecture diagrams and decision history become first-class artifacts in your development process, rather than afterthoughts. For cloud architectures and microservices – which evolve quickly and can be hard to keep in your head – this approach provides a reliable map and journal. The development team can quickly see what the current system looks like (via generated C4 diagrams that can include everything from AWS Lambda and SQS details to context-level overviews) and why it is built that way (via ADRs capturing the reasoning and trade-offs behind choices like “event-driven vs. synchronous APIs" or “serverless vs. containers").

By storing these artifacts alongside the code, you ensure they change when code changes. It’s a safeguard against architecture knowledge siloed in one person’s brain or lost in an outdated wiki. When someone proposes a big change, you can literally diff the architecture – diagrams and ADRs – to see what’s changing. This makes architecture reviews more concrete and historically informed.

For software architects, developers, and DevOps engineers, tools like Structurizr offer a way to practice architecture in an agile, automated manner. The diagrams-as-code model means you can refactor your documentation as easily as refactoring code. ADRs encourage thoughtful deliberation and future accountability for decisions – they create a learning loop for the team. And when it comes to onboarding new team members or collaborating across teams, having a published central source (be it via a Structurizr workspace or a static site) with all the diagrams and decisions is a game-changer.